By Farooq Faisal Khan

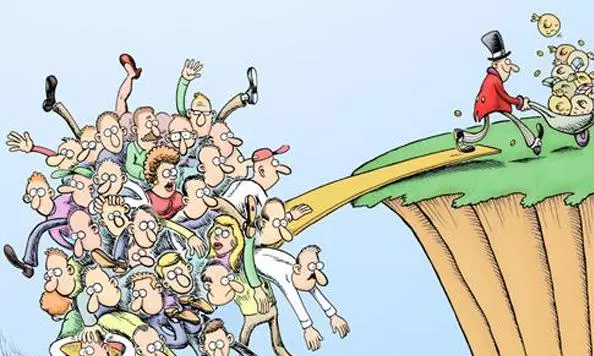

A society becomes dysfunctional when its institutions stop serving the public and begin protecting the interests of a privileged few. When laws are applied selectively, when hard work leads to deprivation and privilege leads to luxury, political science defines such a system as a dysfunctional society.

By this definition, Pakistan’s condition is difficult to deny. One does not need academic expertise to see it. The evidence is visible in daily life, most clearly in the extreme gap between the ruling elite and the ordinary citizen.

On one side stands a powerful elite comprising politicians, senior civil and military bureaucracy, the judiciary, large corporate groups, and now influential media figures. This class enjoys extraordinary salaries and benefits: official residences, free utilities, vehicles, fuel, security, healthcare, education, foreign travel, and generous post-retirement pensions. These privileges are defended as necessity, entitlement, or institutional independence.

On the other side is the common citizen. The officially declared minimum wage of 37,000 rupees often exists only on paper. Inflation continues to erode purchasing power, while electricity, gas, education, and healthcare have become luxuries rather than basic rights. The contrast between elite comfort and public hardship reveals a system designed to protect power, not people.

Institutions meant to serve the public have drifted from their purpose. Parliament has largely become a space for safeguarding personal and group interests. The bureaucracy prioritizes authority and perks over service delivery. Accountability mechanisms function selectively, targeting the weak while shielding the powerful.

Justice, a cornerstone of any functional state, has become inaccessible for most citizens. Courts are slow and expensive. Police stations and government offices inspire fear rather than confidence. When justice appears uncertain or unavailable, public trust in the state steadily collapses—a dangerous condition for social stability.

Education and healthcare, fundamental responsibilities of the state, have been turned into profit-driven industries. Those with financial means secure quality services through private institutions, while the majority are left with underfunded schools and overcrowded hospitals. This deepens inequality and locks generations into disadvantage.

Economic crises further expose the imbalance. The burden of taxation, inflation, and subsidy withdrawals falls almost entirely on ordinary citizens. Meanwhile, elite privileges remain untouched, justified in the name of national interest or institutional sanctity. This double standard breeds resentment and erodes social cohesion.

A functional society rewards effort, ensures justice, and distributes resources fairly. Pakistan increasingly reflects the opposite. Hard work is rarely rewarded, accountability is inconsistent, and public resources flow upward rather than outward.

Until elite privileges, salaries, and pensions are seriously reviewed; until the law applies equally to all; and until ordinary citizens are given real opportunities for a dignified life, Pakistan will continue to operate as a dysfunctional society.