By Farrukh Marghoob

August 6, 1990, marks a significant and dark chapter in Pakistan’s political history. It was on this day that the country’s first female elected Prime Minister, Benazir Bhutto, was unceremoniously dismissed by President Ghulam Ishaq Khan—the so-called “godfather” of the civilian bureaucracy—on allegations of corruption.

However, the charges were nothing more than a smokescreen. The real issue was power: the establishment was simply not ready to accept a democratic government led by Benazir.

The conspiracies against her began the very moment she took oath as Prime Minister. That day serves as a grim reminder that even democratically elected governments in Pakistan are never safe from unelected centers of power, which lie in wait for the right opportunity to strike. (Maryam Nawaz may want to take note.)

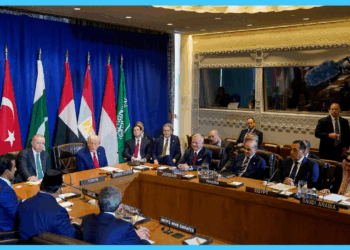

On the evening of August 6, 1990, President Ghulam Ishaq Khan, flanked by the heads of all three armed forces, held a press conference at the Presidency at 5 PM, where he formally announced the dismissal of Benazir’s government—once again, on charges of corruption.

Shockingly, the judiciary later ruled that even newspaper reports could be treated as sufficient evidence of corruption. It’s worth noting that one of the first actions taken by Asif Ali Zardari after becoming president was to scrap Article 58(2)(b), which gave the president sweeping powers to dissolve elected governments.

This was the first such instance post-Zia era where an elected government was ousted, undermined, and forced out of power. Though Benazir won the 1988 elections, the military had only agreed to let her form a government under strict conditions.

Yet, even after she complied, the military establishment never wanted her government to succeed or complete its term. A full-fledged media campaign was orchestrated to discredit her. The press was fed anti-government propaganda, she was labeled a “security risk,” and religious clerics were mobilized to argue that Islam forbade female leadership.

One of Benazir’s biggest “crimes,” in the eyes of the establishment, was inviting Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to attend the SAARC Summit in Islamabad. Her vision was to improve ties with India, resolve conflicts through dialogue, and shift focus from hostility to human development.

But this didn’t sit well with the powers that be. The propaganda machine swung into action, accusing her of “selling out Kashmir.” The reality is that the establishment never wanted better ties with India—then or now. Tragically, India today is ruled by a hardline extremist like Narendra Modi, whose mindset only reinforces the worst fears of the Pakistani establishment.

The dismissal of Benazir’s government triggered a cycle: Nawaz Sharif’s elected government was later removed, followed by Benazir’s second ousting, and finally, General Pervez Musharraf’s 1999 coup against Nawaz Sharif. For eleven years, he ruled the country with unchecked authority.

Regardless of their flaws, elected governments—however inefficient—are never justifiably replaced by military rule. After assuming the presidency, Asif Ali Zardari played a key role in defanging the powers that enabled coups by eliminating the legal backing that allowed such interventions.

Bilawal Bhutto’s role in this effort was also critical, even though it often goes unrecognized. Some argue the constitutional amendments were drafted under military influence. That may be true—but at least the venom was extracted from the snake.

It’s telling—and tragic—that not a single media outlet in Pakistan has commemorated this event or reflected on its lasting implications. Perhaps this article will jog some memories.