MNN (Web-Desk); Just months ago, Pakistan’s global standing appeared diminished saddled with debt, wracked by insurgent violence, and largely sidelined in global geopolitics as Western powers deepened ties with India.

Yet by mid-2025, Field Marshal Asim Munir, Pakistan’s army chief, found himself sharing a private lunch with former U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House, marking a striking diplomatic turnaround barely a month after a brief Pakistan–India military flare-up.

Then came another surprise in late July: Trump imposed 25% tariffs on India, calling it a “dead economy,” while simultaneously celebrating a new trade pact with Pakistan. According to The Economist, this marked a clear shift in American foreign policy that now affects not only South Asia, but also China and the broader Middle East.

The U.S.–Pakistan relationship, once robust but severely strained after Osama bin Laden was killed in Abbottabad in 2011, had been dormant for years. Washington’s exit from Afghanistan further cooled ties.

But the two nations are now rebuilding relations around trade, counterterrorism, and regional diplomacy. American military aid could even resume a significant pivot, given that Pakistan currently sources about 80% of its arms from China.

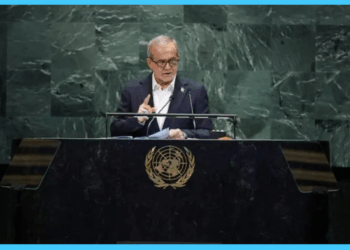

At home, Field Marshal Munir’s stature has grown since the India conflict. The civilian government now commands a two-thirds parliamentary majority, raising speculation about possible constitutional changes that could elevate the army chief to the presidency potentially ushering in a fourth era of military rule since 1947. However, Pakistan’s military spokesman, Lt. Gen. Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry, has dismissed such talk as “nonsense.”

Chaudhry also rejects portrayals of Munir as ideologically extreme. A hafiz-e-Quran and son of an imam, Munir was educated in a madrasa and is the first Pakistani army chief not to have trained in the U.S. or U.K. Despite this, he is described as deeply familiar with the West and firmly opposed to militant Islamist groups — including those India blames for triggering the recent cross-border conflict.

Chaudhry points to Munir’s April 16 speech delivered six days before the Pahalgam attack in Indian-administered Kashmir as a rare moment when the Field Marshal openly expressed his stance. Without claiming responsibility for the attack, Chaudhry said the speech reflected Munir’s readiness to “stand and die” for his beliefs, particularly in the face of rising Hindu nationalism in India.

Observers say Munir is a blend of piety and pragmatism. While devout reportedly praying five times daily he does not mix religion with governance. He is said to admire the reformist policies of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and takes a keen interest in economic revival. Unlike his predecessor, who favored quiet diplomacy with India, Munir is seen as more willing to take risks. Even some critics credit him for resisting international pressure to avoid retaliating against India’s initial strikes.

His elevation to Field Marshal in May drew comparisons with Ayub Khan — Pakistan’s first military ruler and the only other officer to hold that rank. But supporters argue that the current hybrid civil–military arrangement, with a cooperative prime minister and no mandatory retirement age, gives Munir unmatched influence without the need for a coup.

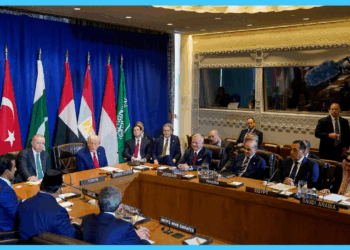

Munir has also earned U.S. praise for operations against Islamic State affiliates in Pakistan. Trump-aligned business figures have reportedly shown interest in Pakistan’s mining and crypto sectors, while Washington sees potential for Pakistan to assist in dialogue with Iran.

In return, the U.S. has softened its criticism of Pakistan’s missile program, resumed some aid, and is considering selling defense equipment like armored vehicles and night-vision goggles. American officials are also reviewing Pakistani claims of Indian involvement in local insurgencies — though skepticism remains.

Munir’s goal, according to officials, is to foster a more balanced, durable relationship with the U.S., while keeping ties with China intact — a delicate balancing act. Economic cooperation with the West is possible but challenged by Pakistan’s investment climate and mutual distrust on terrorism.

As for India, Munir aims to bring New Delhi to the negotiation table. But Prime Minister Narendra Modi remains firm in his stance, warning of military retaliation to any future attacks. When asked how Pakistan would respond, Gen. Chaudhry warned: “We’ll start from the east. They also need to understand that they can be hit everywhere.”

In a volatile region, Pakistan’s future — and much of its foreign policy direction — now hinges on one man: Field Marshal Asim Munir. What he decides could reshape the power dynamics of South Asia for years to come.