ISLAMABAD (Web-Desk); The decades-old Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), long regarded as a cornerstone of water cooperation between Pakistan and India, is now facing its most severe threat yet. India’s recent move to suspend the treaty has triggered alarm bells in Pakistan, which has warned that disrupting water flows could escalate into a full-scale war.

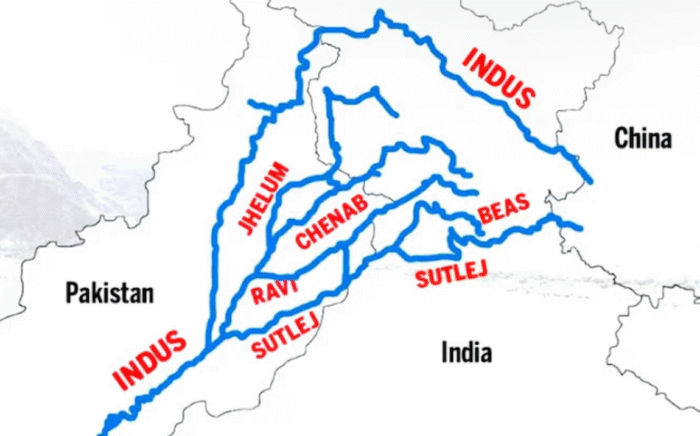

Signed in 1960 under the World Bank’s auspices, the IWT was designed to allocate the use of the Indus River system’s waters between the two nations after Partition. It gave India control over the three eastern rivers — Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej — while Pakistan received the rights to the three western rivers — Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab. The treaty survived wars and tense stand-offs, often hailed as a rare example of functional cooperation amid deep-seated hostility.

But the situation has changed dramatically. As India now threatens to block or divert waters that flow into Pakistan, experts warn of catastrophic consequences. Any disruption could devastate Pakistan’s agriculture, jeopardize food security, and threaten the livelihoods of millions who depend on the Indus Basin’s irrigation networks.

Pakistan’s limited water storage capacity only worsens its vulnerability. Without sufficient reservoirs, the country is ill-prepared to withstand even partial cuts in water flows, especially during winter when river levels are already low.

Yet, analysts point out that India does not currently possess the infrastructure to entirely stop river flows into Pakistan. Large-scale dams or canal systems needed to block or divert the mighty Indus or its major tributaries are not in place. However, even minor diversions or restrictions can hurt Pakistan’s largely agrarian economy.

The Indus River itself is vital. Rising from Tibet’s Mount Kailash at over 5,000 metres, it journeys through the contested Kashmir region before entering Pakistan. Along its roughly 3,000-kilometre course to the Arabian Sea, it collects waters from tributaries like the Kabul and Swat rivers, sustaining vast swathes of farmland across Pakistan’s Punjab and Sindh provinces.

According to Dr. Majed Akhter, a senior lecturer in geography at King’s College London, the Indus Waters Treaty was essentially a “hydraulic partition” following the political one of 1947. “It was needed to resolve issues of the operation of an integrated irrigation system in Punjab, a province which the British invested heavily in and that was partitioned at independence,” he explained.

But water-sharing cannot be divorced from the territorial dispute over Kashmir, which lies at the heart of the Indus basin. Both countries claim the region in full, though they each administer parts of it, and China controls additional segments. “Territorial control of Kashmir means control of the waters of the Indus, which is the main source of water for the heavily agrarian economies of both Pakistan and India,” said Akhter.

The two nuclear-armed nations have already fought three of their four wars over Kashmir, with border clashes continuing. As tensions spike once more over water — the very lifeblood of their people — experts fear the suspension of the treaty could open a perilous new chapter in their fraught history.