Islamabad (Web-Desk) People don’t all age at the same pace. While genetics explains about 25% of the variation in longevity, lifestyle choices and environment largely determine how quickly our bodies — and brains — wear down. Now, an innovative study offers a way to predict an individual’s rate of aging using just a single brain scan taken in midlife, potentially flagging those who might benefit from lifestyle changes to delay or prevent age-related diseases like dementia.

Researchers from Duke, Harvard, and the University of Otago in New Zealand have developed this method based on data from the long-running Dunedin Study. This groundbreaking research followed 1,037 people born in Dunedin in 1972–73, tracking their health through blood pressure, cholesterol, BMI, lung and kidney function, even gum disease, to determine how fast each person was aging biologically.

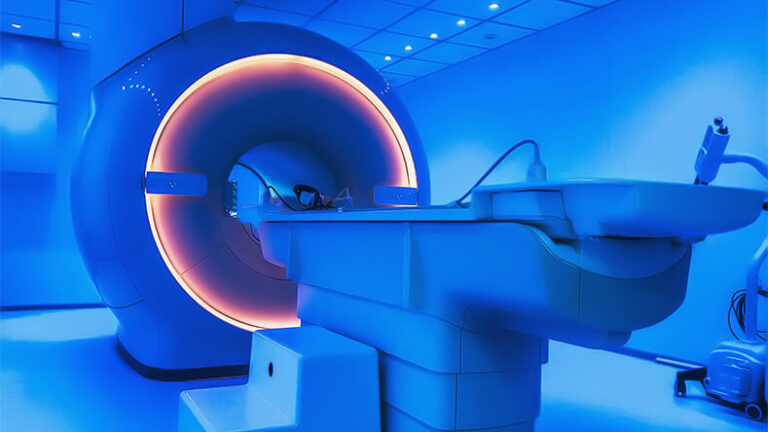

Their new tool, called the Dunedin Pace of Aging Calculated from NeuroImaging (DunedinPACNI), uses MRI scans performed at age 45. By comparing brain scan data with decades of health markers, the team created a score that predicts a person’s biological aging rate — how old their body and brain really are, compared to their chronological age.

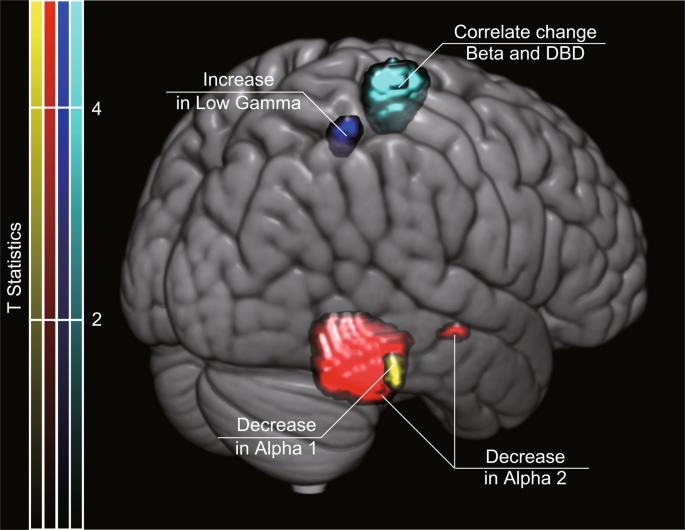

Published in Nature Aging, the study found that higher DunedinPACNI scores, indicating faster brain aging, were linked with weaker muscle strength, poorer balance and coordination, slower walking speed, worse self-rated health, greater cognitive decline, and an older-looking appearance. Those with faster aging brains were also more likely to show deterioration in other systems, like cardiovascular and respiratory health, raising risks of dementia and earlier mortality.

Dr. Madalina Tivarus, an imaging sciences expert at the University of Rochester not involved in the study, called it “very interesting and exciting,” noting it’s one of the first examples where a routine MRI might serve as an aging “check-up.”

The researchers validated DunedinPACNI across major datasets, including the UK Biobank, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, and Latin American Brain Health Institute. They discovered that this tool was often more strongly linked with cognitive and physical decline than traditional MRI measures like hippocampal or ventricular volume.

Dr. Emer MacSweeney, a neuroradiologist at Re:Cognition Health, pointed out how remarkable it is that the brain might serve as a biomarker for overall biological aging. “The fact that brain imaging can reflect systemic aging suggests MRI could provide a non-invasive, accessible window into how the entire body is aging,” she said.

However, experts caution it’s still early days. Tivarus praised the study’s use of rigorous, decades-long data and solid statistics but noted limits: the original cohort was mostly of European ancestry and from a single region, and the tool has yet to be tested widely in younger, more diverse populations. Plus, it estimates dynamic aging processes from a single snapshot.

Still, researchers are hopeful. With people living longer yet not always healthier lives, being able to spot who is on track for accelerated aging in their 40s could allow crucial interventions decades before serious problems like dementia emerge. As the team put it, knowing your biological age could inspire healthier choices — better diet, exercise, and sleep — empowering people to slow or even partially reverse the march of aging before it’s too late.