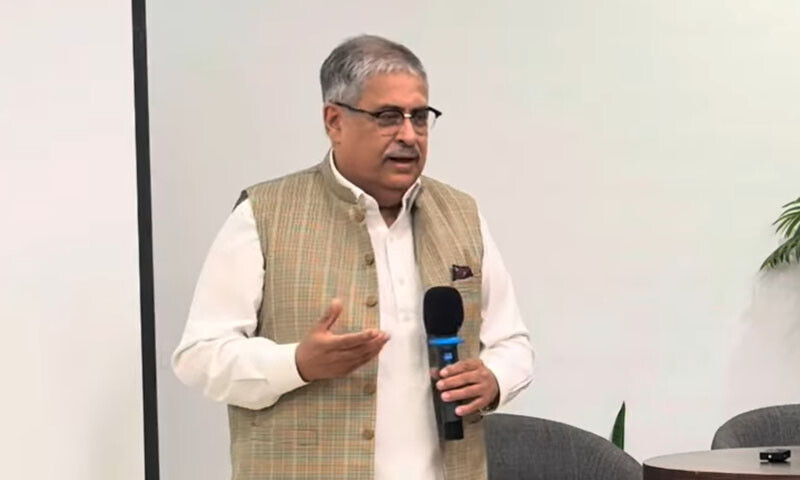

ISLAMABAD; Supreme Court Justice Athar Minallah, while speaking at a documentary screening in Islamabad on Saturday, shed light on the immense challenges judges face in handling cases of enforced disappearances due to the persistent non-cooperation of state authorities and lawmakers. The event was hosted by Defence for Human Rights Pakistan, and Justice Minallah delivered a candid reflection on his experiences dealing with one of the most sensitive human rights issues confronting the country.

Calling such cases “the most difficult” of his judicial career, Justice Minallah explained that whenever courts ordered the recovery of missing individuals, state authorities repeatedly denied knowledge of their whereabouts. “The judge and the court cannot do anything when you don’t have independent investigators,” he said. He further emphasized that every Supreme Court judge bore personal responsibility for the protection of fundamental rights in Pakistan.

Recounting a striking moment from his tenure at the Islamabad High Court, Justice Minallah recalled a child who once appeared in his courtroom with his grandmother. The child, he revealed, was the son of journalist Mudassar Naaru, who went missing in 2018. “His mother had died, and the state had failed even to confirm whether he was alive or dead,” he said. Seeking to highlight the tragedy, he had ordered that the child and grandmother be taken to the then prime minister, as the Constitution makes the executive the guardian of citizens’ rights.

Justice Minallah lamented that courts struggle when the state itself fails to cooperate. “The Constitution clearly says it is the prime minister, the cabinet, and provincial governments who are responsible. You cannot shift the blame elsewhere,” he asserted. He noted that while he had summoned the prime minister at the time, who personally assured Naaru’s son of answers, progress remained elusive.

Reflecting on his time as chief justice of the Islamabad High Court, Minallah said he had made enforced disappearances his top priority and warned the executive that not a single incident would be tolerated in his jurisdiction. Yet, he observed that political leaders tend to ignore the issue once in government, despite acknowledging it while in opposition. He particularly mentioned that students from Balochistan frequently approached his court, highlighting the province’s deep grievances. Although jurisdiction technically lay with courts in Balochistan, he often assumed responsibility, guided by constitutional obligations.

Justice Minallah also underscored the urgent need for an independent judiciary, expressing shame that women from Balochistan were forced to march in the streets demanding their rights. “Those holding exalted offices have not spoken the truth for the last 77 years. The day they begin speaking truthfully, things will change,” he remarked.

His comments came against the backdrop of renewed concern over disappearances. Earlier this month, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan reported that enforced disappearances were fueling alienation and instability in Balochistan. Official data shows that in the first half of 2025 alone, 125 new cases were submitted to the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances, bringing the total to 10,592 cases since its inception.

The Supreme Court itself recently reiterated that it is parliament’s responsibility to address this unlawful practice that has haunted Pakistan for decades.