SKARDU (MNN); As rising temperatures threaten Pakistan’s glaciers, residents in the high-altitude Himalayan region have revived a centuries-old technique known as glacier grafting to tackle water shortages.

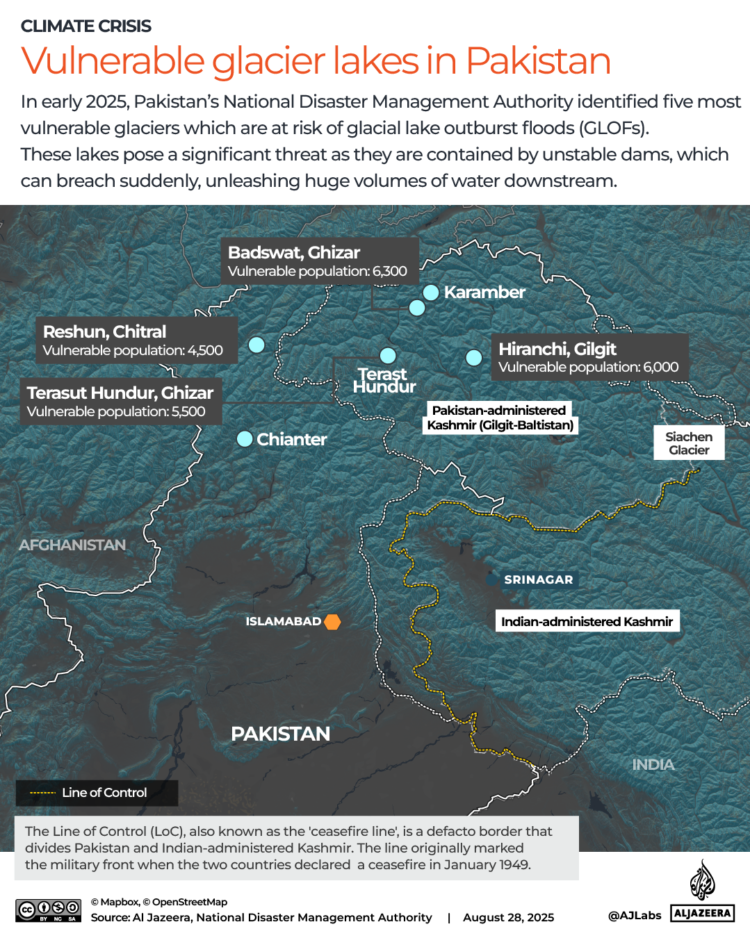

Home to roughly 13,000 glaciers, Pakistan ranks among the ten most climate-vulnerable countries, despite contributing less than one percent to global emissions. The National Disaster Management Authority warned last year that accelerated glacier melting could have significant impacts.

Glacier grafting, locally called “glacier marriage,” involves planting ice in high-altitude locations to create new artificial glaciers. The method dates back centuries, with historical records pointing to the 14th century, when Sufi saint Mir Syed Ali Hamadani grafted a glacier in Giyari village to block invaders from Yarkand, according to Zakir Hussain Zakir, professor at the University of Baltistan, Skardu. Over time, the technique evolved to address water scarcity in fragile mountain ecosystems.

Similar practices exist in India’s Ladakh region, where modern adaptations like “ice stupas” are used to preserve water during climate change.

How Glacier Grafting Works

Glacier grafting uses “male” and “female” ice from different valleys. Volunteers collect approximately 200 kg of each type of ice and transport it to designated sites. Traditionally, ice was carried in wooden cages along steep, narrow mountain paths.

Materials required include coal, grass, salt, and water from seven streams. Before starting, volunteers recite Quranic verses, perform rituals, and follow strict cultural practices. Plastics are avoided, only local food is consumed, and no harm is caused to living beings.

At the grafting site, ice is layered in trenches with male ice on the right and female ice on the left, mixed with coal, salt, and grass. Water from the streams is dripped over the layers to bind them. Over months, the layers fuse into a single ice mass. Seasonal snowfall gradually forms an artificial glacier, which, after surviving at least three years, becomes a stable water source. Site selection is critical: north-facing slopes, less sun exposure, strong winds, and protection from flowing water are essential.

Spirituality, Discipline, and Community Work

Zakir Hussain Zakir emphasizes the spiritual and cultural aspects of glacier grafting. Ice must never touch the ground and must remain in motion from collection to planting. Volunteers maintain strict discipline: no talking, no plastic use, no consumption of non-local foods, and they pass ice baskets without lying down.

Traditionally, the process concludes with Gang Lho songs dedicated to the glacier, treating it as a living being. Villagers often pray with tears in their eyes, hoping the artificial glacier will secure water for their communities.

A successfully grafted glacier can supply water within two decades. However, experts warn that climate change, inadequate snowfall, or armed conflicts can endanger the process. Military presence and activity in the glaciers, including bullets and equipment movement, may damage the ice.

Since the 1950s, Pakistan’s mean temperature has risen by 1.3°C, twice the global average, increasing the urgency for glacier grafting. Yet, younger generations are less engaged in this traditional practice due to urban migration and alternative livelihoods, threatening the intergenerational transfer of knowledge.

Glacier grafting remains a vital, culturally rooted method for sustaining water supply in Pakistan’s high mountains, illustrating the power of indigenous knowledge and collective community effort.

Source: Al Jazeera, Report by Ijlal Haider and Faras Ghani; Produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.